Chapter 2: The Arras-Cambrai road, September 1914-August 26, 1918 (Scroll below for pictures)

The Arras-Cambrai road has seen a lot of action during the Great War and it is the scene of the action in this book. It’s pertinent to give some of the history of the fighting on this front.

Early in the war, in September 1914, German troops actually reach Arras, but do not stay. In October, during the race to the sea, the situation got hotter. The Germans arrived from the Marne via the village of Riencourt-lez-Cagnicourt, and head full force towards Arras. On the way, they occupied the village of Vis-en-Artois on the Cambrai road and then collided with the French Army who were on the Monchy-le-Preux hill and the Wancourt ridge. These heights, with the villages of the same name, fell to the Germans: The French retreated to the outskirts of Arras. The Germans pursued and took Tilloy-lez-Mofflaines (the last village before reaching Arras) but were stopped at the faubourg Saint-Sauveur (an Arras suburb) by the Alpine soldiers of the Barbot Division. With this stalemate before Arras, the Germans undertook flanking movements to the North, which would ultimately take them to Belgium.

Arras found itself on the front line, and under siege, with the front line at Tilloy-lez-Mofflaines on the Cambrai road, only a few kilometers from downtown Arras. The Paris-Arras railway line was disrupted.

On the German side, the villages on the periphery of Arras (Tilloy, as well as Beaurains and Saint-Laurent-Blangy) were in German hands as well as the high ground: Telegraph Hill near Beaurains as well as the Wancourt ridge (Wancourt Tower to the British) and Monchy-le-Preux hill. The sector dug in for a long stretch of trench warfare.

The relative clam was broken on September 25, 1915, during the 2nd Battle of Artois, fought to the North of Arras, overflowed into the sector at Tilloy. A diversionary attack against Beaurains and Telegraph hill, to support the Anglo-French offensive at Vimy and Loos fails. The sector returns to the relative calm of trench warfare.

In January, 1916, the President of the French republic, Raymons Poincaré, visted the front at Tilloy. He travelled from the train station in Arras and went up a communication trench that went through the faubourg Saint-Sauveur. He left us his impression of his visit in his book Verdun 1916:

We got to Arras, which is more and more devastated. There are almost no intact houses left. We leave our cars at the train station which is terribly ravaged. We visit close to there, in a shelter, behind the wall of a house, a battery of 75s.[1] Then, via a communication trench[2] paved with red brick, we head out to the front lines to the East of Arras. The front line is manned by Regiments of the XVII Corps, including the 11th.[3] Dug in to sandy soil which resists humidity, they have a sharp bearing. I stop quietly at a listening post, but I hear absolutely nothing.[4]

In March 1916, the British Army relieve the French in the sector. Under new management, the horror of trench warfare continues until the spring of 1917.

In March of 1917, as part of their retirement on the Somme (operation Alberich) the Germans abandoned Beaurains. The front East of Arras now went through Tilloy, then Telegraph hill and the village of Neuville-Vitasse.

On April 9, 1917, the great Arras offensive began. On the Tilloy front, the British advanced up the Cambrai road and took Tilloy, Telegraph Hill, Neuville-Vitasse and then Monchy-le-Preux and Wancourt. For a short time, they even occupied the village of Chérisy, a penetration of more than seven kilometers. However, the occupation of Cherisy was fleeting as it fell back into German hands and the battle raged until mid-May, without appreciable gain. For almost a year the new front-line East of Arras was now beyond Monchy-le-Preux, in front of Chérisy. With the heights of Monchy and Wancourt in Allied hands, a normalcy descended on Arras. Train service to Paris, disrupted since 1914, is reestablished.

The calm on the Arras-Cambrai road is broken again on March 21, 1918, when the Germans launched their spring offensive on the Somme. On their right flank, the Germans take Croisilles a village a few kilometers south of Neuville-Vitasse. This turn of events has a crucial; impact on the Arras-Cambrai road. In fear of being outflanked, the British on Monchy-le-Preux and Wancourt abandon their positions and retire to Tilloy-lez-Mofflaines.

On March 28, the Germans extend their right flank to the North and attack Arras. Like in 1914 the Germans are stopped at Tilloy one kilometer from the 1914 front line. Arras was safe, and it was the last German incursion against Arras in the war.[5] After all the human capital spent it must have been discouraging for both sides to see the front line one kilometer from where it had been in 1914.

The New Offensive at Arras, August 26, 1918.

The middle of August 1918, the Canadians were on the Amiens -Montdidier front having just participated in an offensive to clear the Paris-Amiens railway. The front having been stabilized after a week of heavy fighting, the Canadians were relieved from the sector by the French Army and were immediately reassigned to the Arras front. Thus, began the logistical nightmare of moving the 100,000-strong Canadian Corps North to the new area of operation.

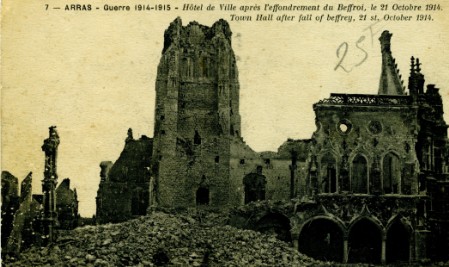

In August 1918 the city of Arras, as we have seen, has been on the front line for almost four years. Apart from a brief visit by German troops in 1914, the city avoided the German occupation. The city is in ruins. Her magnificent belfry is destroyed, and the Flemish buildings of the two main squares are in ruin. Most of the civilian population has been replaced by soldiers of the British Empire. The war is so close a traveler need go barely three kilometers from downtown to reach the front line.

There was no respite for the Canadians. They were destined to open a new offensive, this time from Arras towards the city of Cambrai. It would take 6 weeks and 7,000 dead before reaching Cambrai, a mere 30kms away down the Arras-Cambrai Road. I call this stretch of highway Canada's Highway of Heroes.

The first phase of this great advance would be remembered as the 2nd Battle of Arras of 1918. This Battle would be broken down into two separate operations, the Battle of the Scarpe, 1918[6] (August 26th to August 30, 1918) and the Battle of the Drocourt-Quéant Line (September 2-3, 1918).[7] The goal of the Battle of the Scarpe was to push the Germans back from Tilloy-lez-Mofflaines, down the Cambrai road to the edge of the Drocourt-Quéant line (or Wotan Stellung to the Germans.) at Haucourt. With this accomplished, the pressure would be off Arras and direct rail service to Paris could be restored.

The object of the Battle of the Drocourt-Quéant Line was to breach the imposing system of defences on a six-and-a-half front astride the Arras-Cambrai road between Sensée river, in the North and Quéant, in the South.[8] Once the Drocourt-Quéant Line was breached it was planned to exploit through the breach and capture the bridge of the Arras-Cambrai road over the canal du Nord, and secure a beachhead beyond. In the end the Drocourt-Quéant Line was breached, but the Germans destroyed all the bridges over the canal. The crossing of the canal du Nord was postponed to the 27th of September.

The battlefield merits some description: South of the Scarpe river, the Drocourt-Quéant Line was protected by what was effectively a ten kilometer-wide stretch of no-man’s land (a relic of the 1917 fighting), which served as an advance guard to the mighty Drocourt-Quéant Line. Many valleys cross the battlefield and were used to good effect defensively. The Sensée valley can be traced through the villages of Fontaine-lez-Croisilles, Chérisy, Vis-en-Artois, Haucourt, Rémy, Éterpigny, Étaing, l’écluse, Hamel and Palluel. The valley of the Hirondelle is not as long and follows the villages of Saudemont, Rumaucaourt and Écourt-Saint-Quentin. The Cojeul valley follows the villages of Saint-Martin-sur-Cojeul, Héninel, Wancourt, Guemappe et then connects with the Sensée valley at Étaing. The scenic Scarpe valley runs through Feuchy, Fampoux, Roeux (all famous places in 1917) Pelves, Plouvain and Biache-Saint-Vaast. The Trinquise valley goes from Biache-Saint-Vaast to Lécluse by going through Hamblain-lez-Prés. The canal du Nord runs from Arleux, in the North, through Palluel, Sauchy-Cauchy, Marquion, Sains-lez-Marquion, Inchy-en-Artois and Moeuvres to points South. The important pieces of high ground were Monchy-le-Preux, Wancourt, Mont Dury and, on the other side of the canal du Nord, was the heights of Oisy-le-Verger.

On this new front, the Canadians, reinforced by British Divisions, faced the German 17th Army, which was planning on remaining in Cambrai for the winter. The clash to settle whether that would come to pass would begin on August 26th, 1918, in an operation that would be remembered, as we have seen, as the Battle of the Scarpe, 1918. Only the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Divisions were available on the 26th, the 1st Division being in transit and the 4th was concentrated in a large wood called Gentelles near Boves, 11kms from Amiens.

The 4th Division was the last to leave the Amiens front. It did not do so until the 27th of August, well after the battle began. (The infantry of a Canadian Division was organised into three Brigades of four Battalions each. The 4th Division contained the 10th, 11th and 12th Infantry Brigades, the 10th Brigade, which is of most concern to us, was composed of the 44th, 46th, 47th and 50th Battalions.)

The Canadians took up their positions in Tilloy-lez-Mofflaines, and Beaurains, and after a spirited preliminary action, took Neuville-Vitasse. The main offensive began at 3 AM on the morning of August 26th accompanied by a devastating artillery barrage. In Écourt-Saint-Quentin, a village 21kms behind enemy lines, School Mistress Clémence Leroy notes in her journal the ferocity of the bombardment:

-Monday 26 (August 1918)

What a night! Since 3 A.M.[9] it’s impossible to get any shut-eye; there is a terrible bombardment between Bapaume and Lens[10]. Great explosions are shaking everything around us and this persists all day.

Clémence is unaware that the Canadians of the 2nd and 3rd Divisions have assaulted and captured the strategic villages of Wancourt and Monchy-le-Preux respectively. The Arras front was on fire.

The result of the opening day of battle was that, on August 26th, Ecourt-St-Quentin was 21kms behind enemy lines. By nightfall it was only 15. The Canadians were coming.

[1] A ‘75’ is a 75mm French artillery piece.

[2] After M. Poincarré’s visit, the trench was named Président Poincaré Trench.

[3] The 11th Regiment, of the French 33rd Division was from the Department of Tarn-en-Garonne.

[4] This was taken from the book Sur l’axe stratégique Arras-Cambrai-Tilloy-lès-Mofflaines-Monchy-le-Preux, edited by the Cercle archéologique arrageois in 1999.

[5] The Germans came back in 1940 and fought a tank battle against the British at Beaurains.

[6] Not to be confused with the Battle of the Scarpe of 1917.

[7] Phase 2 of this great advance down the Arras-Cambrai road to Cambrai (the Battles of the Canal du Nord and Cambrai) is beyond the scope of this book. See Tough as Nails, Michel Gravel, CEF Books, 2006 for more on these operations.

[8] The portion of the Drocourt-Quéant Line between the Sensée and the community of Drocourt (a suburb of Lens) was only breached on October 11, 1918. Douai was liberated a few days later. In fact, most people don’t realise that after the Breaking of the Drocourt-Quéant line on September 2-3, 1918, the Western Front ran West-East from Biache-Saint-Vaast on the Scarpe River, through Hamblain-les-Prés and Sailly-en-Ostrevent, on the Trinquise river up to L’écluse and Palluel in the Sensée marshes. Between September 3 and 27, 1918, the front turned a sharp right towards the south along the Canal du Nord to Moeuvres on the edge of the Canadian front. From Moeuvres the front line connected to the Hindenburg line which, in September, was still intact.

[9] Clocks in occupied France were set to Berlin Time which was one hour ahead of the rest of the country. Therefore, in her diary, all times stated by Clémence Leroy are Berlin Time. For consistency I converted all these references to reflect the time in Free France.

[10] Ecourt-Saint-Quentin was at the centre of the British operations on the Western front. Bapaume is 25kms South, and Lens, 30kms North.